“The science is dangerously clear.” – Joe Biden, COP27.

The 27th world climate change conference, known as COP27, kicked off in Sharm-El Sheikh last week. Over 30,000 attendees from around the world gathered to discuss and debate the climate crisis. Here, we are going to break down the good, the bad, and the ugly from the conference and see how we have progressed since COP26 in Glasgow last year.

Rocky Beginnings

Even before starting, COP27 was seeing some turbulence. In late October, Downing Street announced that UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak would not be attending the summit due to ‘pressing domestic commitments’. Although he did end up attending, other important world leaders didn’t.

China’s Xi Jinping, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, India’s Narendra Modi, and the US’s Joe Biden were conspicuously absent from the group picture at the summit. It was India and China that were named at the last minute at COP26 on the international agreements that have been reached by Alok Sharma. Ironically, these are the nations that produce the most CO2 across the globe, emitting just under 22 billion emissions in 2021. Biden arrived later in the conference, due to mid-term election commitments, but the absences were a harsh reminder of how split the world still is on its dedication to fighting climate change.

Another COP27 naysayer was famous climate activist Greta Thunberg, who stated that she saw the conference as ‘greenwashing’.

Safe to say, COP27 was going to be an eventful one.

A Call to Action

A big theme surrounding the conference this year has been urgency. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres described the world as a ‘chronicle of climate chaos’, and stated that we are on a ‘highway to climate hell with our foot on the accelerator’.

In his speech, Rishi Sunak, urged world leaders not to see the invasion of Ukraine and the current energy crisis as reasons to move away from climate focus, but to accelerate action.

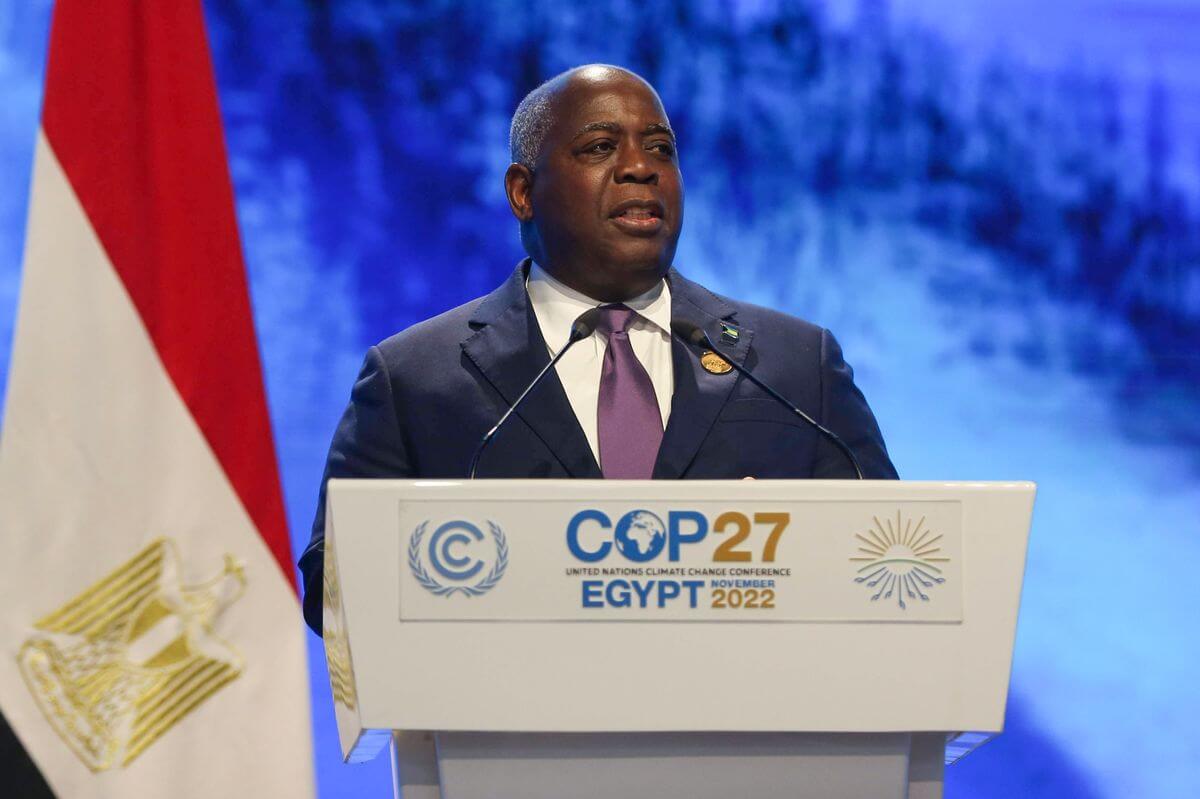

There has also been a focus on how more fortunate countries can help those struggling with climate disaster. Philip Davis, PM of the Bahamas, which has seen a barrage of climate-related extreme weather incidents, stated that they ‘will not give up’ and that their only alternative is ‘a watery grave’.

Just during the conference, hundreds of millions have been pledged by more developed countries to help less fortunate nations implement climate crisis strategies and infrastructure, the US being one of these donors pledging $150 million to fund climate adaptation across Africa. But let’s face facts, $150 million is a drop in the ocean for the changes needed to accelerate Africa to a renewables only continent.

The Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) has called on fossil fuel companies to share their side of the burden and pay a tax on the ‘extortionate’ profits they have been making at developing countries’ expense. The countries within AOSIS are low-lying, making them far more vulnerable to the rising sea levels and extreme weather events caused by global warming. This is the first time that the idea of financial compensation has been broached in the nearly 30 years since the conference began.

The Fossil Fuel Divide

One of the most controversial subjects at COP27 has been fossil fuels. Although there is plenty of talk about how the world must move away from its dependence on fossil fuels and implement renewable energy solutions, that hasn’t really been translating into concrete action.

Disconcertingly, research by Global Witness found that over 600 people at COP27 have ties to fossil fuels – a 25% jump compared to COP26. Although leaders across the world have committed to implementing more renewable solutions, the fact that a large chunk of the conference is directly linked to the fossil fuel industry is cause for concern.

Despite the climate crisis worsening before our very eyes, fossil fuel usage is continuing to rise. BP made a profit of £7.1 billion between July and September, and Shell made £8.1 million, showing that the world is still deeply wedded to oil and gas as the main energy source.

Similarly, it was revealed that the registered delegate for Mauritania was Bernard Looney, a chief executive at BP (the company has major investments in the west African nation). Many have expressed dissatisfaction that so many of the conference’s attendees and delegates have direct ties to oil and gas, as these industries are widely responsible for the climate disaster the world is facing today.

To some, the representation of these corporations at COP27 is an opportunity for change and innovation, but to many it is just another reminder of how dependent we still are on fossil fuels, even if they signal our destruction.

COP26 to COP27 – What Was Promised and What Was Delivered

A year on from COP26 in Glasgow, how the world has progressed and met the targets set has come under great scrutiny. The overall sentiment? We are not moving fast enough.

On the monetary side, the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), which was created at last year’s conference, has seen some trouble. The coalition of financial institutions once equaled a whopping $130 trillion, but now some major institutions are threatening to leave the alliance. Bank of America, JP Morgan, and Morgan Stanley have all threatened their exit from GFANZ, meaning the now $150 trillion would take a significant hit.

There’s also the net-zero commitment gap. While the Glasgow summit saw a massive increase in countries vowing to lower their output, 11% of global emissions are still unaccounted for, meaning no countries are taking responsibility for them. It’s easy to talk, it’s easy to make these commitments, but the actual delivery on them has been painfully slow, to the point where the 1.5C warming limit could be beyond our reach.

Like net-zero, other commitments from COP26 have been missed. This includes deforestation, and leaders from 145 committed last year to halting and reversing deforestation by 2030. This is now looking unlikely, as the practice is still hitting record levels.

However, there may be some hope. Brazil, which contains much of the Amazon rainforest, recently appointed its new president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in a historic win against former far-right president Jair Bolsonaro. Whilst Bolsonaro was shockingly pro-deforestation and ushered in record levels of destruction, Lula has vowed to save the Amazon and pledged to end deforestation in Brazil.

What It All Means for the Future

In a year as eventful as 2022, it was expected that COP27 was going to be just as packed with debate and controversy. The illegal invasion of Ukraine, the energy crisis, and growing inflation and threat of recession have all taken away focus from climate action. However, as Sunak said in his speech, these events should be reminders of how we need to accelerate our response to the changing climate.

COP27 covered a great many things. It reflected on the past, and set goals for the future. But the one thread that has gone throughout is that we are still moving too slowly. The climate crisis is happening now, and we need to implement rapid positive change in order to achieve the future we want – what we believe we deserve.

Share your thoughts

No Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.