Urbanisation is increasing, and it’s doing so at an unprecedented rate. By 2050, two thirds of the world’s population are expected to be living in cities, alongside a population increase from 7.7 billion to 9.7 billion. How these cities interact with nature is absolutely crucial. Disconcerting statistics show that in the 50 years leading up to 2020, wildlife populations fell overall by 68%. These numbers could be expected to rise unless decisions are made and rapid change occurs. A synergy must be found between the concrete metropolises humanity has created, and the natural world that we inhabit, before this planet reaches the dangerous tipping point.

In June 2021, the UK government issued an amendment proposal to the Environmental Bill in response to the Dasgupta Review on The Economics of Biodiversity. In this proposal, Town and Country Planning Act developments and Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects in England will need to deliver something called Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) – where natural environments will need to be left in a measurably better state than beforehand. As per the proposal, a development’s BNG will need to be at least 10%.

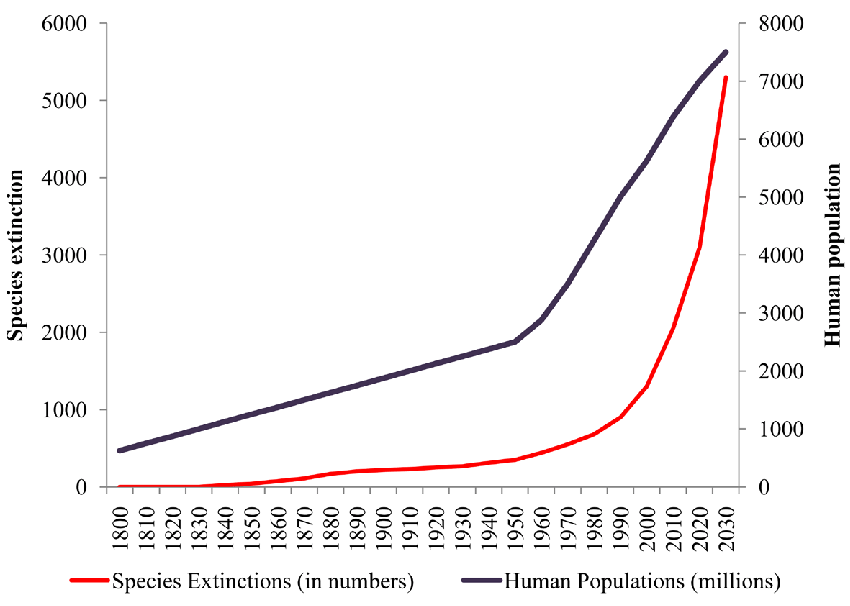

The government has rolled out the Biodiversity Metric 3.1, a tool for developers to calculate the biodiversity impacts of their projects. Rapid urban development is drastically damaging the natural habitats of flora and fauna, leading to a significant increase in species extinction (as shown on the graph below). The aim of BNG is to repair that damage.

Corporations need to take decisive action in order to mitigate the impact the urban world has on nature. In April, Canary Wharf Group (CWG) announced their partnership with the Eden Project to dramatically diversify the landscape of the docks. Assisted by award-winning architects Glenn Howells, the bulk of the project is going to introduce a ‘green spine’ through Canary Wharf. This will include parks and gardens, floating pontoons, and waterside access to promote arts, culture, and activities. The project is about reinventing the space, changing attitudes on how people view cities; repositioning them as concrete jungles of convenience no longer, and instead spaces where collaboration, culture, and the natural world can be celebrated and incubated.

CWG has been seen as a leader in sustainability and biodiversity practices in the UK. Currently, their park and garden space equals 20 acres, and the estate is home to 5km of waterside paths. CWG has also achieved a 49% reduction in both Scope 1 and 2 emissions since 2012. As stated by Eden Project Chief Executive David Harland, the partnership is an opportunity to “bring nature back to other urban developments in the UK and across the globe.”

When looking at urban biodiversity, a successful example is Shenzhen. What 40 years ago was a fishing village, Shenzhen is now China’s third most populous city with 12.59 million inhabitants, and is also one of the most biodiverse urban areas in the world. 78,000 hectares of forest cover the city, which is also home to 25 nature-protected areas equalling 494.43 square kilometres, a stunning 24.75% of the city’s total area. Its skies are affectionately called ‘Shenzhen blue’, a nod to its high air quality composite index, which ranked sixth among the 168 key Chinese cities.

Shenzhen is also a sponge city, something discussed in a previous article. In short, sponge cities are urban areas with an abundance of natural spaces. These spaces absorb heavy rainfall, preventing flooding and reducing wastewater. Shenzhen has been implementing sponge city concepts since 2004, with a focus on water retention, storage, and recycling.

Shenzhen also operates on a zero carbon model. Chinese enterprise OCT Group plans to invest 50 billion yuan (approximately £6 billion) to build a low carbon demonstration park to promote culture, tourism, and urbanisation, as well as to provide a strategy for zero carbon across the city. Using artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things (IoT), the development aims to significantly reduce carbon emissions, particularly those surrounding construction. The overall goal is to increase these sustainability efforts across China, opening up further zero carbon cities and urban units, via continuous regulation by cloud-based smart management centres.

There is also Johor, described as Malaysia’s Forest City, a twenty-year project announced in 2006 to build an offshore city that is low-polluting, land-conserving, and energy efficient, with all roadways underground. Originally aimed at wealthy Chinese citizens, the ambitious project has suffered a fair few hurdles on the road to completion. Economic uncertainty and political tensions between China and Malaysia have hung over the project and, by the end of 2019, only 15,000 units in the city had been sold, opposed to the 700,000 unit target. Despite this, the project is expected to be finished in 2035.

There appears to be an unspoken understanding that loss of biodiversity is a given consequence of rapid urban development. This thought process is outdated and dangerous.

Urbanisation and biodiversity do not have to be mutually exclusive, and significant efforts to make city spaces across the globe greener are essential. Although there are some biodiverse developments in place, progress, like with many other topics surrounding climate change, is far too slow. Promises of carbon neutral and positive environmental spaces can no longer be empty. Immediate action must be taken if the world wants to keep global temperatures from rising to irreparable heights.

Share your thoughts

No Comments

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.